The recent UK Supreme Court decision on the Equality Act 2010 has created a sharp legal distinction between the UK and Australia regarding the recognition of sex and gender in anti-discrimination law. In the UK, the Supreme Court ruled that ‘woman’ and ‘sex’ in the Equality Act refer strictly to biological sex as observed at birth, not gender identity — even for those with a gender recognition certificate (GRC) under the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (which is subordinate to the Equality Act).

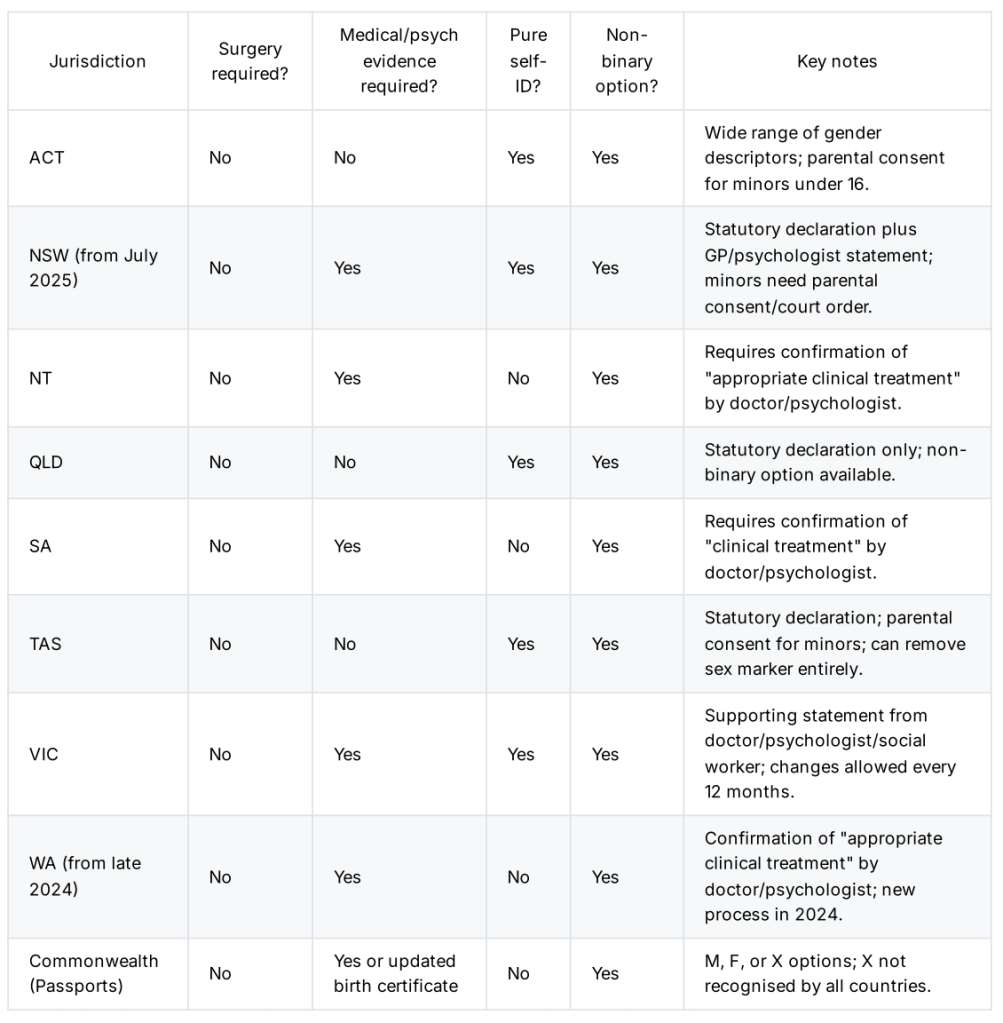

The interpretation of Australia’s Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) (SDA), by contrast, is marked by ambiguity and confusion. Australia does not have GRCs; instead, states and territories have adopted sex self-identification regimes (‘self-ID’, see the table, below), allowing individuals to change the sex marker on their birth certificate and other official documents through an administrative process. This means a person born male can, by self-declaration, become legally female and access female-only spaces and services, including toilets, changing rooms, crisis centres, and sporting competitions.

The difference is rooted in statutory language and legal interpretation. The UK Supreme Court has clarified that ‘sex’ in the Equality Act refers exclusively to biological sex. In Australia, the SDA has never defined ‘sex’ as in the past the ordinary, common meaning of the term applied as a concept understood to be based in biological reality; however, before amendments were made to our SDA in 2013, the Act did define ‘woman’ and ‘man’ and did relate those definitions to biological sex; this was before the definitions were repealed and before confusion arose as to what sex meant. In other words, a definition of sex before the 2013 amendments did not exist because a definition simply wasn’t needed.

Today, however, with non-biological understandings of sex being introduced into the legislative and policy environments, the interpretation of ‘sex’ is left to case law and administrative guidelines, creating operational confusion and undermining sex-based protections for women and girls. In the case of policy implementation by government departments — which affects Australians on a daily basis — many follow advice provided in the Australian Government’s Guidelines on the Recognition of Sex and Gender (2013) and prioritise gender identity for most administrative and service purposes (Section 16, and see, for example, Victorian Department of Health, Services Australia, and the Australian Bureau of Statistics). Sex is only considered where explicitly necessary, and even then the Guidelines’ own biology-based definition of sex does not bind courts (unlike the UK’s statutory interpretation), and cannot override the SDA or its judicial interpretation.

This creates a paradox, as the SDA — despite not, and never, containing a statutory definition of sex — nevertheless has exemptions for single-sex spaces (e.g., Section 30) that remain tied to biological sex on the ordinary, common meaning of the term. While Section 30 of the SDA allows service providers to exclude individuals based on sex if it is “reasonably necessary” for privacy, decency, or other prescribed reasons, this threshold is vague and untested in cases involving people who have changed their legal sex marker through self-ID. (The recent Tickle v Giggle Federal Court case did not resolve the meaning of ‘sex’ under the SDA, as the judge’s comments on the effect of a changed birth certificate were obiter dicta — not binding precedent — and the case was decided on gender identity discrimination grounds, not sex discrimination.) This legal uncertainty undermines the clarity and effectiveness of sex-based protections, and has led to a chilling effect on public debate and on the willingness of organisations to enforce policies for female-only spaces.

In short, while the UK now offers legal certainty by anchoring sex-based rights and protections firmly in biological reality, Australia’s patchwork of self-ID laws, government guidelines, and the SDA’s silence on core definitions have left service providers, women, and the public in a state of confusion. Until Australia’s lawmakers address this ambiguity, the balance between gender identity inclusion and sex-based protections will remain unsettled-leaving the most vulnerable women and girls at risk and the law open to challenge.